Jeanguy Saintus and his Ayikodans dance troupe still struggle against formidable odds

From the Miami Herald

A year after a triumphant Miami performance, Jeanguy Saintus and his Ayikodans dance troupe still struggle against formidable odds.

A year after a triumphant Miami performance, Jeanguy Saintus and his Ayikodans dance troupe still struggle against formidable odds.

By Jordan Levin

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A year ago, Miami greeted Haitian choreographer Jeanguy Saintus and his Ayikodans dance company with an outpouring of support and goodwill that promised to be transformative.

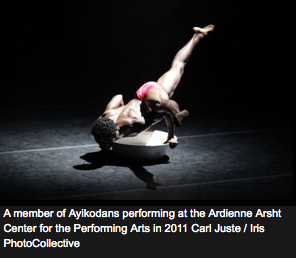

Moved by Saintus’ determination and his dancers’ incandescent artistry in the face of the 2010 earthquake that had damaged the company’s home, the Adrienne Arsht Center and a coalition of Miami community leaders organized a fundraising concert that yielded $117,000.

The money enabled him to pay his dancers, keep his school open and work towards this weekend’s concert at the Arsht Center, where Ayikodans will premiere a dance commissioned by the center in three sold-out performances.

“It was really a great help to not only have people respect what you do but to invest in it,” Saintus says from his home in Port-au-Prince.

“What last year brought to me is the confidence to know I have a work I can do, and I don’t have to worry ‘OK, can I do it?’ We are very grateful for what the Arsht Center has done, for the support of the people in Miami.”

And yet the hopes raised here a year ago underline the long-term difficulty of Saintus’ mission in Haiti, where the desperate need to house, feed and provide medical care for people continues to dominate.

“What we do here has a social and economic impact,” Saintus says. “Now everyone is talking about tourism, about projecting a different image of Haiti overseas. This is what we’ve been doing for years. And yet all the money goes to people who are feeding children, to the [nongovernmental aid organizations], not to the arts or what we do.”

Miamians were moved by Saintus and Ayikodans’ artistry, a combination of Haitian folkloric and religious dance with contemporary technique and ideas, performed with breathtaking intensity and virtuosity.

“We learned from Ayikodans and Jeanguy about a spirit of survival and determination that far exceeds the challenges of life here in the U.S. and in Miami,” says John Richard, president of the Arsht Center.

“To do something so well, to survive and to represent an entire culture and people fighting for their lives. We saw this as a wonderful chance to help … in presenting what we think is world-class dance.”

In addition to his company, Saintus runs a dance school and scholarship program, often feeding, clothing and housing poor students. His most famous graduate is Vitolio Jeune, who studied at Miami’s New World School of the Arts, performed on the hit TV show So You Think You Can Dance and is now a member of the renowned Garth Fagan Dance Company.

When Ayikodans tours outside Haiti, it projects a rare positive image of the country. Yet Saintus says he finds little support or recognition for his efforts at home.

“Even our president is always begging for money. When people come here we take them to Cite Soleil [a notorious slum]. So at the end the world only knows about political turmoil and poverty in Haiti.”

Babacar M’Bow, a curator, editor and regular visitor to Haiti who last year created an exhibition and book about art in Haiti after the earthquake, says that Saintus makes some important points.

Art can play a potentially valuable role for a country without natural resources or industrial infrastructure, says M’Bow, who spoke last week on a panel at the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami about the island’s culture post-earthquake.

“Haiti is a super-power of art and culture in the Americas,” he says. “How can you rebuild a country by putting aside its most meaningful resource, for which it has attained world recognition? Art is the only field in which Haiti has been recognized around the world. Therefore any meaningful search for salvation cannot ignore these resources.”

Haitian painters and dance companies attract positive attention, whether through tourism or donations, that can help the country address its desperate material needs, says M’Bow.

“You cannot do everything at the same time. There has to be a scale of priorities. But art and culture have to be part of that scale somehow. The ministry of culture should have ways to take its dancers around the world, because that’s what people respond to.”

Despite Saintus’ frustration, the pieces Ayikodans will perform in Miami express his bedrock belief in Haitian culture and the possibilities of community effort.

Danse de L’Araignee (Dance of the Spider), created with the Arsht Center commission, is based on images and ritual music for the vodou spirit Gede Zarenyen.

“We don’t die in vodou, instead we have all these beautiful gedes,” says Saintus. He interprets Zarenyen as potentially dangerous, like a poisonous spider, but also as representing the power and joyfulness of community.

“It’s more a message about unity and togetherness,” he says. “I am trying to show the importance, the urgency of what we are doing as choreographers in creating for others, in saying what others don’t want to say.”

The other work is an expanded staging of Anmwey Haiti Manman (Cry Haiti Mother), which Saintus created in the aftermath of the earthquake. As calls poured in from friends outside the island, asking if he and his company were OK, Saintus says he felt paralyzed and despairing, his studio badly damaged by the quake, his dancers and students scattered. A few weeks later, he began to express his feelings with three dancers.

“We were telling our stories, how we survived the day of the earthquake,” he says. “Manman [the mother] is the main thing in Haiti, most of us Haitians don’t have fathers. If something happens to you, you say ‘Oh mother.’ That’s why I say ‘Cry Haiti Mother.’ Since we are all in that pain, calling mama, but what can this mother do for us, she is totally destroyed.”

Expressing those desolate feelings gave Saintus the strength to conquer them. “That voice, that scream inside, when you are still in shock, it’s very difficult to let go,” he says. “This piece made me realize I was still a choreographer, and that dance was still alive.”

Last year’s Arsht Center benefit has opened other doors for Saintus. He taught at the University of Florida in Gainesville and at the Cleo Parker Dance Company in Denver, for which he is also slated to create a new dance. Ayikodans is being considered for a major New York dance festival this year.

Al Crawford, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater lighting designer who created lights for Ayikodans’ Arsht Center show last year, is repeating the favor this year. Crawford traveled to Haiti to meet with Saintus, which encouraged the choreographer greatly.

“Al said something wonderful, that the first time he came because they asked him to come and help, but this year he comes back to Haiti because he has people he loves and beautiful dancers here,” Saintus says.

Saintus too is driven by the dancers and the art form he loves.

“It’s too late for me to give up,” he says. “I believe in what I am doing for these boys and girls. Like the one I am not taking to Miami. He needs to perform there next year. When you get that feeling, you think you are doing something. Sometimes you want to say ‘I have done enough.’ But I am not giving up. It is too late to give up.”

Read more here: http://www.miamiherald.com/2012/05/18/v-fullstory/2808583/jeanguy-saintus-and-his-ayikodans.html#storylink=cpy

Read more here: http://www.miamiherald.com/2012/05/18/2808583/jeanguy-saintus-and-his-ayikodans.html#storyBody#storylink=cpy

Search

Featured

| » | See how the Green Family Foundation NeighborhoodHELP program at FIU changes lives |

| » | Purchase Alan Lomax In Haiti: Recordings For The Library Of Congress, 1936-1937, nominated for two GRAMMY Awards. |

A Documentary by Kimberly Green

A Documentary by Kimberly Green

| » | View Trailer |

| » | Learn More |

| » | Watch GFF President Kimberly Green's CGI Stories segment about the music of Alan Lomax. |